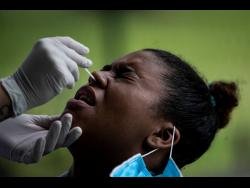

Experts say testing is the best way to determine what you have since symptoms of the illnesses can overlap.

The viruses that cause colds, the flu and COVID-19 are spread the same way – through droplets from the nose and mouth of infected people. And they can all be spread before a person realizes they’re infected.

The time varies for when someone with any of the illnesses will start feeling sick. Some people infected with the coronavirus don’t experience any symptoms, but it’s still possible for them to spread it.

Cough, fever, tiredness and muscle aches are common to both the flu and COVID-19, says Kristen Coleman, as assistant research professor at the University of Maryland School of Public Health. Symptoms specific to COVID-19 include the loss of taste or smell.

Common colds, meanwhile, tend to be milder with symptoms including a stuffy nose and sore throat. Fevers are more common with the flu.

Despite some false portrayals online, the viruses have not merged to create a new illness. But it’s possible to get the flu and COVID-19 at the same time, which some are calling ‘flurona’.

“A co-infection of any kind can be severe or worsen your symptoms altogether,” says Coleman. “If influenza cases continue to rise, we can expect to see more of these types of viral co-infections in the coming weeks or months.”

With many similar symptoms caused by the three virus types, testing remains the best option to determine which one you may have. At-home tests for flu aren’t as widely available as those for COVID-19, but some pharmacies offer testing for both viruses at the same time, Coleman notes. This can help doctors prescribe the right treatment.

Laboratories might also be able to screen samples for various respiratory viruses, including common cold viruses. But most do not have the capacity to routinely do this, especially during a COVID-19 surge, Coleman says.

Getting vaccinated helps reduce the spread of the viruses. The US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says it is safe to get a flu and COVID-19 shot or booster at the same time.

Do at-home COVID-19 tests detect the omicron variant?

Yes, but US health officials say early data suggests they may be less sensitive at picking it up.

US government recommendations for using at-home tests haven’t changed. People should continue to use them when a quick result is important.

“The bottom line is the tests still detect COVID-19 whether it is delta or alpha or omicron,” says Dr Emily Volk, president of the College of American Pathologists.

Government scientists have been checking to make sure the rapid tests still work as each new variant comes along. And this week, the Food and Drug Administration said preliminary research indicates they detect omicron, but may have reduced sensitivity. The agency noted it’s still studying how the tests perform with the variant, which was first detected in late November.

Dr Anthony Fauci, the top US infectious disease expert, said the FDA wanted to be “totally transparent” by noting the sensitivity might come down a bit, but that the tests remain important.

There are many good uses for at-home tests, Volk says. Combined with vaccination, they can make you more comfortable about gathering with family and friends.

Can your pet get COVID-19?

Yes, pets and other animals can get the coronavirus that causes COVID-19, but health officials say the risk of them spreading it to people is low.

Dogs, cats, ferrets, rabbits, otters, hyenas and white-tailed deer are among the animals that have tested positive, in most cases after contracting it from infected people.

While you don’t have to worry much about getting COVID-19 from your pets, they should worry about getting it from you. People with confirmed or suspected COVID-19 should avoid contact with pets, farm animals and wildlife, as well as with other people, according to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“If you wouldn’t go near another person because you’re sick or you might be exposed, don’t go near another animal,” says Dr Scott Weese at Ontario Veterinary College.

Not all infected pets get sick and serious illness is extremely rare. Pets that show symptoms typically get mildly ill, the CDC says.

Some zoos in the US and elsewhere have vaccinated big cats, primates and other animals that are thought to be at risk of getting the virus through contact with people.

This particular coronavirus most likely jumped from animals to humans in the first place, sparking a pandemic because the virus spreads so easily between people. But it does not easily spread from animals to people. Minks are the only known animals to have caught the virus from people and spread it back, according to Weese.

Three countries in northern Europe recorded cases of the virus spreading from people to mink on mink farms. The virus circulated among the animals before being passed back to farmworkers.

How easily animals can get and spread the virus might change with different variants, and the best way to prevent the virus from spreading among animals is to control it among people, Weese says.

How will the world decide when the pandemic is over?

There’s no clear-cut definition for when a pandemic starts and ends, and how much of a threat a global outbreak is posing can vary by country.

“It’s somewhat a subjective judgement because it’s not just about the number of cases. It’s about severity and it’s about impact,” says Dr Michael Ryan, the World Health Organization’s emergencies chief.

In January 2020, WHO designated the virus a global health crisis “of international concern.” A couple months later in March, the United Nations health agency described the outbreak as a “pandemic,” reflecting the fact that the virus had spread to nearly every continent and numerous other health officials were saying it could be described as such.

The pandemic may be widely considered over when WHO decides the virus is no longer an emergency of international concern, a designation its expert committee has been reassessing every three months. But when the most acute phases of the crisis ease within countries could vary.

“There is not going to be one day when someone says, ‘OK, the pandemic is over,’” says Dr Chris Woods, an infectious disease expert at Duke University. Although there’s no universally agreed-upon criteria, he said countries will likely look for sustained reduction in cases over time.

Scientists expect COVID-19 will eventually settle into becoming a more predictable virus like the flu, meaning it will cause seasonal outbreaks but not the huge surges we’re seeing right now. But even then, Woods says some habits, such as wearing masks in public places, might continue.

“Even after the pandemic ends, COVID will still be with us,” he says.

Why can’t some COVID-19 vaccinated people travel to the US?

Because they might not be vaccinated with shots recognised by the US Food and Drug Administration (FDA) or the World Health Organization (WHO).

When lifting overseas travel restrictions in November last year, the US required adults coming to the country to be fully vaccinated with shots approved or authorized by the FDA or allowed by WHO.

Among the most widely used vaccines that don’t meet that criteria are Russia’s Sputnik V vaccine and China’s CanSino vaccine. Sputnik V is authorised for use in more than 70 countries while CanSino is allowed in at least nine countries. WHO still is awaiting more data about both vaccines before making a decision.

Vaccines recognized by the FDA and WHO undergo rigorous testing and review to determine they’re safe and effective. And among the vaccines used internationally, experts say some likely won’t be recognized by the agencies.

“They will not all be evaluated in clinical trials with the necessary rigour,” said Dr William Moss, executive director of the Johns Hopkins International Vaccine Access Center.

An exception to the US rule is people who received a full series of the Novavax vaccine in a late-stage study. The US is accepting the participants who received the vaccine, not a placebo, because it was a rigorous study with oversight from an independent monitoring board.

The US also allows entry to people who got two doses of any mix-and-match combination of vaccines on the FDA and WHO lists.