The women detained at the for-profit jail in the small, rural town of Jena, Louisiana, hail from all corners of Latin America. Some are asylum-seekers who fled repressive regimes. Others are lawful U.S. permanent residents who were picked up by immigration authorities after serving time in prison. Some are mothers and even grandmothers.

Right now, they’re all terrified.

Like many of the more than 35,000 immigrants currently in U.S. Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) custody, the women held at the LaSalle detention center in Jena feel powerless to shield themselves from the highly contagious coronavirus, which has killed more than 60,000 people worldwide, including more than 7,000 in the U.S. At least 370 people have died in Louisiana alone, where a recent surge in cases has threatened to overwhelm the state’s health care system.

With at least eight confirmed cases among detainees nationwide and six among detention center employees, ICE has come under intense pressure to drastically downsize its detainee population to mitigate the risk of outbreaks.

But detainees and their advocates fear ICE isn’t acting quickly enough. Despite some releases, many of them compelled by a flurry of lawsuits, the agency has resisted calls to implement a nationwide policy of releasing some categories of detainees, including older immigrants, those with chronic medical conditions and asylum-seekers who don’t pose a threat to the public.

Desperation among detainees has grown. Last week, officials at the Jena facility pepper sprayed women detainees who tried to leave a housing area during a briefing on coronavirus preparations. But seven women who were there said the jail staff failed to address their concerns about lax social distancing and hygiene practices, prompting a small group to start protesting. ICE spokesman Bryan Cox said the four women who were pepper sprayed “became disruptive and confrontational,” and “attempted to physically force their way out.”

The incident last week was one of several in which officials at ICE detention centers used pepper spray to disperse protesting immigrants.

The women detained at the Jena jail are alarmed by news reports on Telemundo and Univision announcing rising death tolls in the U.S. every day. Their families tell them how much the pandemic has upended the world outside the walls of their crowded housing area, and they feel trapped and endangered.

As the U.S. confronts a public health crisis unlike any it has ever faced, the women at the Jena jail fear the public is forgetting about them — and they are pleading with a crisis-stricken nation to listen to them.

“Give us an opportunity to be with our families. We’re mothers,” Ana, a 46-year-old Dominican immigrant, told CBS News in Spanish during a phone call from the Jena facility. “Don’t let us die like this, as if we were animals. We’re human beings.”

“We can die inside here”

Arlet Victoria Remón Pérez, 23, has been in U.S. immigration custody since April 2019. But she has never been as scared as she is now. “We know the virus is killing a lot of people, and we are very susceptible to contracting it,” Remón Pérez told CBS News in Spanish. “Once one person is infected, we’re all going to get sick.”

“If that happens here … I think many of us will die,” she added.

Before fleeing Cuba, Remón Pérez finished two years of medical school. She said the staff at the detention center has not taken the necessary steps to protect everyone inside the facility. Access to soap, hand sanitizer and disinfecting equipment is very limited or non-existent, she added.

Social distancing, Remón Pérez said, is impossible, noting that she sleeps in a housing area that holds roughly 80 other women, and the bunk beds are less than a meter apart. Their diet consists mainly of carbohydrates like bread and pasta and lacks nutrient-rich foods to boost their immune systems.

Remón Pérez fled her country last year after being threatened by government security forces because of her father’s political advocacy and her identity as a lesbian woman. She and her partner, Eliana Hecheverría, crisscrossed Central America and Mexico to reach the U.S. southern border, where they were placed on a waiting list to tell U.S. officials about the persecution they fear in Cuba. But after weeks of waiting in Mexico, the motel in Ciudad Juárez where they were staying was taken over by drug cartel members, prompting them to cross the U.S. border illegally in April 2019.

The couple was detained near El Paso for about two months. They were allowed to shower and brush their teeth every 10 days, Remón Pérez said. The long hours in the sweltering Texas desert were difficult for Remón Pérez, who suffers from severe asthma. In June 2019, the couple was transferred to the detention center in Jena.

Remón Pérez does not blame the women who tried to leave the housing area last week — everyone is desperate. “They were only protesting because we were afraid. It was not fair what they did to those women,” she said. Cox, the ICE spokesman, said the women were placed in solitary confinement for violating facility rules.

“We’re scared because we know we can die inside here,” Remón Pérez said. “The situation does not bode well for us. We don’t have a way to protect ourselves. We feel like children who are protected by parents. They are in charge of protecting us — and they are not protecting us.”

Her partner, Hecheverría, said the only way they will be able to protect themselves from the coronavirus is if ICE releases them. “I don’t feel like the owner of my own life here, because here, I’m completely at risk. Outside, I know how to take care of myself, I know how to protect myself, I know what I have to do to not get infected,” she added. “Here, I don’t.”

Hecheverría is particularly worried about the health of her partner. In addition to having chronic asthma and severe allergies, Remón Pérez said she has not menstruated for seven months. She said a doctor near LaSalle found cysts in one of her ovaries, but that she has yet to be taken to the hospital again to determine whether the cysts are malignant. Cox, from ICE, said he could not discuss Remón Pérez’s medical treatment without her consent.

Both Remón Pérez and Hecheverría are appealing asylum denials by judges at the Jena immigration court, which has rejected over 90% of the asylum requests it has received this fiscal year, according to the Transactional Records Access Clearinghouse. They don’t have criminal records, but the government won’t allow them to continue their proceedings outside detention because it has determined they might fail to show up at their court hearings.

Asked about the concerns raised by the seven women interviewed by CBS News, Cox called them “unsubstantiated rumors.” He said all meals are developed by a registered dietician and referred CBS News to information on ICE’s website about measures taken in response to the pandemic. “All persons are screened upon arrival at ICE facilities, soap and other appropriate cleaning supplies are provided to those in custody, and all persons in custody are provided necessary and appropriate medical care,” Cox wrote in a statement.

A spokesperson for GEO Group, the private prison company that runs the Jena jail, said staff have taken “comprehensive steps” to mitigate the risk posed by the coronavirus pandemic. “We strongly reject these unfounded allegations, which we believe are being instigated by outside groups with political agendas,” the spokesperson added.

“They’re desperate to get out of here”

Last week, Marlene Seo, 48, watched a television news segment that discussed extraordinary efforts people are undertaking for their pets during the pandemic. She seemed stricken.

“They get a thought aired on TV and news, yet the immigrants don’t,” Seo told CBS News during a phone call. “If our congressmen and everybody, even the president, is talking about humanity, and us keeping together and doing the best that we can to help each other, why are we not being treated in that sense?”

ICE said it has implemented screening protocols for new detainees. But Seo said the constant flow of people, both immigrants and staff, entering and leaving the jail in Jena is what concerns her the most.

“People keep coming in and out. They’ll deport people,” she said. “And they’ll take them out and they’ll bring them back within a week because there are no flights.”

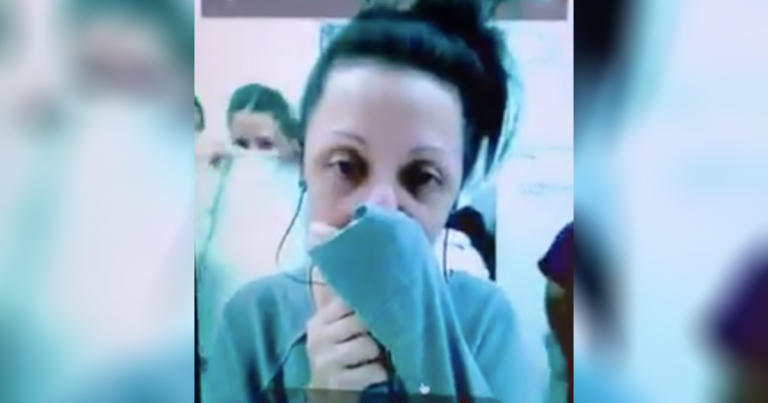

Courtesy Alexandra Seo

Seo said the staff has not provided detainees cleaning supplies, despite repeated requests, and social distancing is not being enforced. She has noticed staff working while sick.”Everything that applies to everyone on the outside doesn’t apply to us in here,” Seo added. “We are allowed to be 80 [people] grouped together, sneezing, coughing.”

Unlike most of the immigrants at Jena, which holds roughly 1,200 ICE detainees, Seo speaks fluent English. She was born in Mexico but has lived in the U.S. since she was 3 years old. The green card holder was arrested by ICE upon completing a year-long prison sentence for filing a false corporate income tax return.

Like other permanent residents at Jena and other ICE detention centers, Seo continues to be detained beyond her criminal sentence because the government wants to deport her to Mexico. “I don’t know Mexico. I’ve never been to Mexico,” she said. “I’ve been here all my life.”

Seo is determined to try to stay in the U.S. and return to her family in Denver, especially now, during the pandemic, but she said the past couple of months have been difficult. “It’s been too long. I’ve missed my granddaughter’s birthday. I missed two granddaughters being born.”

She has found some solace in helping the other women detainees. The grandmother said the women at the detention center turn to her when making requests to ICE because she speaks and writes English fluently. Many immigrants and asylum-seekers who have been detained for months and even years, Seo said, have recently been requesting that ICE send them to their home countries or allow them to pay for their own flights to leave the U.S.

“They’re desperate to get out of here,” she said.

Kenni, 25, is one of those women who has grown increasingly desperate. Last week, she was placed in solitary confinement after the pepper spray incident.

Because Kenni applied for asylum at an official border crossing after waiting for three months in northern Mexico, the young Cuban asylum-seeker is not eligible for bond in immigration court. The ICE field office in New Orleans, which has been sued for its very low parole approval rate in recent years, has also denied her request for parole.

“It’s been seven months of imprisonment without having committed any crime,” Kenni said.

She’s scared of contracting the coronavirus while in detention, and like the other women at Jena, there’s no sign she’ll be freed.